Film Review: Revolution - New Art For A New World

As Albert Einstein once said: “The Revolution introduced me to art, and in turn, art introduced me to the Revolution!”. Indeed, much the same could be said for the Russian Revolution of 1917, the 100th anniversary of which is being marked by the BBC this November with range of TV and radio broadcasts in a Russia-themed season.

While BBC Four delves into the art, architecture and music of the period, a selection of commissioned programmes examine this significant historical event and its continued impact on society.

‘Revolution - New Art For A New World’, a feature documentary film that has been produced by award-winning British film director Margy Kinmonth to be broadcast on BBC Four, reveals the avant-garde art movement that flourished after the October Revolution, only to be stifled by Joseph Stalin.

Kinmonth, who is currently the director for Foxtrot Films (www.foxtrotfilms.com) and received the ‘Creative Originality Award’ at the Women in Film and Television Awards back in 2009, certainly packs a lot in this film. It follows ‘War Art with Eddie Redmanye’ (2015), which was shown on ITV and depicted artists of World War One. Separately, her series Naked Hollywood with Arnold Schwarzenegger won BAFTA's documentary series.

To date she has directed four major films about Russia. And, her latest documentary sees top actors in the shape of Tom Hollander, known for drama films such as Enigma, Gosford Park, and Pride & Prejudice, portraying leading protagonists of the time.

It draws on the art collections of major Russian institutions, contributions from contemporary artists and performers who provide personal testimony of their descendants. One is Fedor, the grandson of Aristarkh Lentulov (www.wikiart.org/en/aristarkh-lentulov), a major Russian avant-garde artist with a Cubist orientation, who is interviewed in the same apartment where he worked hundred years ago. In so doing Kinmonth has sought to bring to life the artists of the Russian avant garde.

We also, for example, hear from Mikhail Piotrovsky, Director of the State Hermitage Museum (www.hermitagemuseum.org/) in St Petersburg, the oldest museum in the world, who talks about the revolution around Tsar’s Winter Palace being “planned like the French Revolution.”

The year 1917 was a defining and pioneering point in time for cinema and Kinmonth discovered unseen rare film footage of the Russian Avant-Garde era in the film archive at Krasnogorsk. Getting into to rare works of art inner the museums, which most folk are restricted from seeing was an added for plus Kinmonth in her endeavours to get under hood of the events around a century ago in Moscow and St Petersburg, the latter named Petrograd at the time.

The Russian Revolution of 1905, which is said to have been a major contributing factor to the Russian Revolutions of 1917, by contrast was crushed.

After setting the scene about the state of play in Russia with comments read by Lenin (who agreed with Marx that 'Religion is Opium For The People') , she narrates historical developments since 1861, when serfdom was abolished in the country (although the peasants - around 80% of Russians - had no rights), through the growing discontent in the years leading up to First World War against Tsar Nicholas II until the two revolutions happened in February and October 1917.

Artists were at the vanguard of the movement - fighting at the barricades. While the court photographer captured an aristocratic era that was fast ending, before the Tsar’s entire family (Romanovs) were executed by firing squad and thrown down a mineshaft.

The year 1917 was a pioneering period for the cinema itself and rare, unseen footage in the Russian State Documentary Film & Photo Archive at Krasnogorsk (russianarchives.com/gallery/krasno/), of the Russian Avant-Garde movement was seen by Kinmonth. he archive holds film footage dating back to Nicholas II's coronation plus photographs and photo albums from the 1850s onward. It was a year later the capital moved from St Petersburg to Moscow.

The film epic 'October' (1928) by Sergei Eisenstein, a story which was in itself served as a propaganda exercise immortalizing the political events, is referenced at the start of Revolution. However, while the film's version of events with the storming of the Winter Palace were what the Bolsheviks wanted, it was far from actual reality given that there was no storming. But as they say, why let the facts get in the way of a good story. Art was used through the film lens to spread the Communist's message and ideology.

And, there are some stunning shots in Revolution of the Winter Palace in St Petersburg and Red Square in Moscow.

Interestingly, while long before 1917 there was a huge community of artists in the country, it took the political movements around the revolution to spark a massive outpouring of creativity. The director wanted also to provide context to the artistic and political developments that occurred.

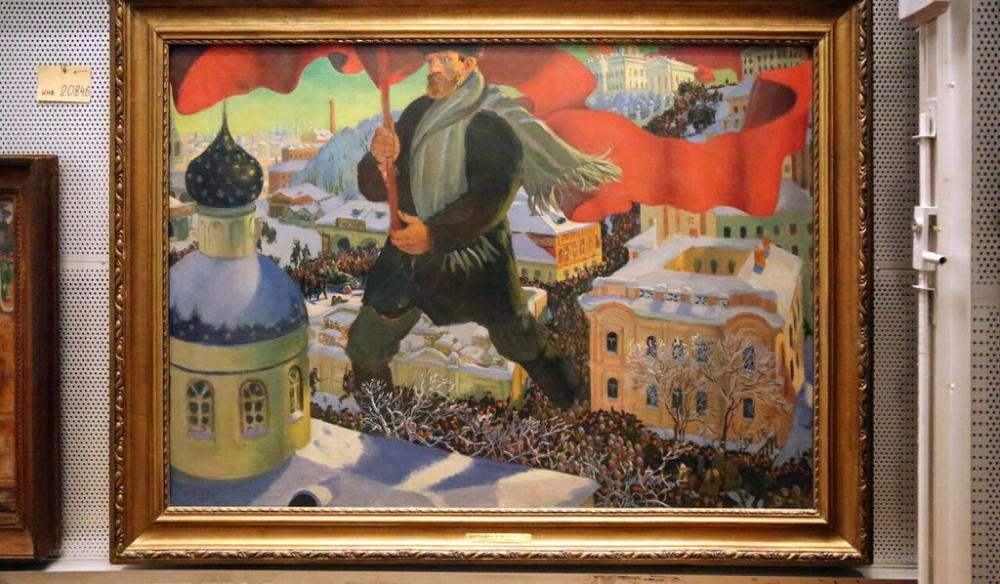

Art historian and international curator Zelfira Tregulova, director of Moscow’s largest museum, the State Tretyakov Gallery (www.tretyakovgallery.ru/en/), is interviewed and opined that between 1900 and 1915 Russian avante-garde artists were “the best artist in the world.” The various paintings certainly stand out on screen.

Revolution features the voices of some of the most exciting actors at work today, who portray the key players of the Russian revolutionary period of the Avant-Garde movement. Vladimir Lenin is played by Macfadyen, BAFTA award-winning English actor, while Hollander plays Kazimir Malevich, dubbed as "a giant" in the avant-garde space by Tregulova. James Fleet, Eleanor Tomlinson and Daisy Bevan add to the cast as artists Wassily Kandinsky, Lyubov Popova and Varvara Stepanova.

Malevich is nevertheless described as a "crazy man" by Andrei Konchalovsky, a Russian film director and screenwriter, who was a frequent collaborator of Andrei Tarkovsky earlier in his career. He had studied for ten years at the Moscow Conservatory, preparing for a career as a pianist. However, in 1960 he met Tarkovsky and co-scripted his movie 'Andrei Rublev' (1966). He is the grandson of painter Pyotr Konchalovsky (1876-1956), a member of the Jack of Diamonds group.

Remarking on Malevich's artwork, Konchalovsky said: "Certain pieces I like but Black Square (painted in the summer of 1915) is absurd... although considered a masterpiece." The painting is a symbol that represented the new beginning in Russia. Malevich, an idealist and not in reality according some art commentators, said of one his paintings: "I have put colour and knots in it."

The commentary on the art itself proves fascinating as do the sad endings of many of the artists’ stories. As such the art of Revolutionary Russia deserves to be seen.

‘Revolution - New Art For A New World’ will be broadcast in the BBC’s upcoming Russian Revolution Season and on Monday, 6 November at 9pm on BBC Four, with its premiere at the Curzon Bloomsbury and Curzon Mayfair on 10 November 2017. For a trailer see: www.youtube.com/watch?v=ShSD-3TLuxg

About the author: Roger Aitken is a freelance writer who contributes to Forbes (www.forbes.com/sites/rogeraitken) amongst other titles and was a former FT staff writer. He was awarded a press prize from the Czech Republic on the 25th anniversary of the 'Velvet Revolution' for helping to promote the country as a tourist destination through his work.